September 26, 2012

The Queensland Ombudsman has released a scathing report highlighting departmental mix-ups and critical decisions in the lead-up to Cougar Energy starting its trial underground coal gasification (UCG) project at Coolabunia.

Ombudsman Phil Clarke investigated the issuing of an environmental authority for the project, including the associated conditions, and the monitoring of the project up to June 30, 2010.

He made 16 recommendations, (see box below), in a report which he has handed to State Parliament.

- Download a copy of the Ombudsman’s Report (553kb PDF)

- An explanation of the UCG process at Coolabunia (862kb PDF)

The investigation focused on the actions of the relevant departments but did not cover the suitability of the actual site or the events after June 30, 2010 – which are the subject of three court actions.

“The investigation was an autopsy-style review of … the approval and oversight of the project by the relevant departments,” Mr Clarke wrote.

The departments put under the microscope were:

- Department of Environment and Heritage Protection (DEHP), formerly the Department of Environment and Resource Management (DERM), and the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), and the

- Department of Natural Resources and Mines (DNRM), formerly the Department of Employment, Economic Development and Innovation (DEEDI), and the Department of Mines and Energy (DME).

Mr Clarke said he had carefully considered whether to publish the report in light of the ongoing court proceedings.

“In my view there is a significant public interest in disclosing the matters detailed in the report to allow informed public discussion and debate of the matters under consideration rather that waiting for the finalisation of litigation (which may be a significant time away),” he said.

The State Government announced on January 28 last year that the Coolabunia trial – which had been temporarily halted after a well casing failed – would not be allowed to re-start. It has alleged traces of benzene and toluene detected in nearby groundwater were linked to the project.

No Environmental

Impact Statement

A turning point in the assessment process was a decision in December 2007 to describe Cougar Energy’s initial Mineral Development Licence (MDL) application as a “Non-Standard” application.

“Standard” applications require an Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) to be prepared; this was not mandatory for “Non-Standard” applications.

Cougar Energy’s “Non-Standard” application was reviewed by the EPA’s regional office which recommended no EIS was required.

Mr Clarke had concerns about both the decision not to require an EIS, and also the adequacy of the EPA’s policy on the circumstances in which an EIS was required.

He also expressed concerns about apparent inconsistencies in the EIS guidelines:

I am concerned that the procedural framework does not sufficiently provide for MDL activities that have a potentially significant or highly uncertain environmental impact.

“I have concerns about the policy expressed in the EIS guideline of only requiring an EIS for an MDL where there is a high probability of a significant impact on a matter of State or national significance.

“I consider that in certain circumstances, this test is simply too high and does not adequately account for a MDL, albeit one of a small scale, that has the potential to have significant environmental impact or where its impacts are sufficiently uncertain.

“This is my view is particularly significant for situations involving novel or emerging technologies, or those previously unused in Australia, where there is an unknown risk or high risk of environmental impact. In my view the policy is inadequate to provide environmental protection in such situations.

Mr Clarke stopped short of finding that an EIS should have been obtained in Cougar Energy’s case but he said he “had some concerns” in relation to how the assessing officer and the EPA’s Co-ordinated Assessment Committee (CAC) had confidence ruling no EIS was required.

Mr Clarke said it was not clear sufficient consideration had been given to

- The unexpected high level of impact on a range of environmental values

- The uncertainty about the nature and extent of possible impacts on the environment

- The unexpected community concern with the project.

Mr Clarke said environmental impacts could be significant, even from a small, one-off project.

“The scale of the project (or the pilot nature of it) should not be the sole determining factor for an EIS where potentially significant and/or uncertain environmental impacts are associated with a pilot activity,” he said.

However he admitted that an EIS would not have altered the ultimate outcome of the Coolabunia project; his concerns related to the adequacy of the assessment.

Lack Of Experienced Staff

Mr Clarke also expressed concerns about lack of experienced staff in the departments under review.

The assessment committee was currently under review “due to the departure of experienced officers”. At the time Mr Clarke did his interviews, this “assessment committee” consisted of a single officer and he was told: “all the experts we used to rely on aren’t there anymore”.

He noted that several departmental officers had commented on the “recent significant loss of expertise” from within DEHP with experienced officers either retiring or leaving for jobs in the mining, petroleum and gas industries.

“The departure of experienced staff should be a matter of concern for DEHP. For a regulatory agency whose officers need significant experience to engage in regulatory activity to achieve agency goals, the loss of expert staff has significant ramifications,” Mr Clarke wrote.

He also expressed concern that EPA officers assessing a draft Environmental Management Plan submitted by Cougar were not able to locate an expert in groundwater.

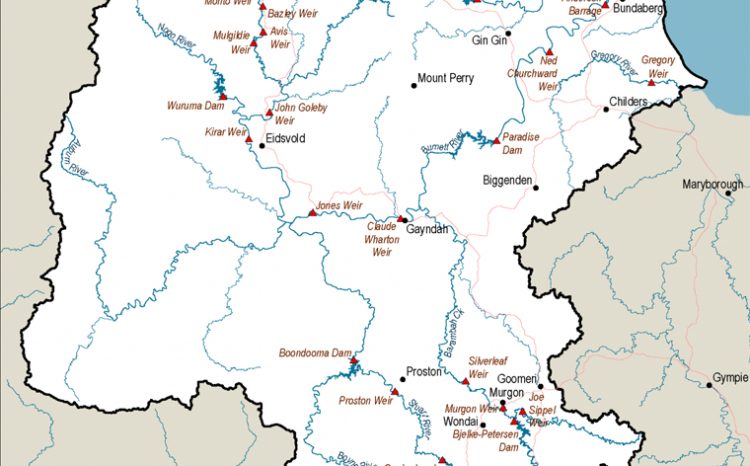

They had sought advice from the then-Department of Natural Resources and Water in Bundaberg (later to become part of DERM, and now DNRM) without determining if the people they consulted had expertise in the specific area in which the advice was sought, ie groundwater science.

“My concern is that no one with with expertise in groundwater science had input into the setting of the conditions for the environmental authority in a situation where several agency officers, including the officer responsible for conducting the assessment and preparing the conditions, believed it was necessary to obtain that input,” Mr Clarke wrote.

Recognition of Possible Community Concerns

The EPA’s assessment report noted there was a potential for “nuisance issues” (odour and noise) for the six residences within the MDL area.

“Residents may also have other concerns. For example. as many of the farms in the area use groundwater for stock watering and in some cases drinking water, they may have concerns regarding the effects of the UCG facility on groundwater,” the EPA report stated.

However despite this assessment by the EPA, there was no formal public notification process required prior to determining Cougar’s application.

And despite this lack of public notification, the EPA noted it had not been approached by any members of the public with specific concerns.

“It is not clear what weight was placed on this lack of community concern,” Mr Clarke wrote.

“However, given that there was no formal public notification required or undertaken prior to the determination of the application for an environmental authority, and therefore no method by which the community would necessarily be aware of the proposal, it would be unreasonable if a lack of any approach by members of the community with specific concerns regarding the project was considered as a positive factor in favour of the project.”

Mr Clarke said he could not reconcile the expected impacts of the project – which included water quality, water discharges, hydrology issues, groundwater, land erosion/stability, land rehabilitation and subsequent land use – with the decision not to notify people potentially affected by the project.

Ironically, if the project had required an EIS, public notifications would have been required.

The Departmental response to Mr Clarke’s report stated: “It is not practicable for all resource activities to be publically notified, and that this would impose excessive and onerous regulatory burdens, often with little benefit”.

Other Concerns

Mr Clarke also expressed concern that:

- Cougar Energy’s expert adviser was permitted to set the “safe” level of contaminants in the groundwater without any oversight from the department.

- An EPA assessment for a financial assurance – a bond – to be lodged by Cougar Energy suggested $1.5 million. This would cover the cost of rehabilitation of the site should the company prematurely cease operations. Cougar suggested $465,000. An internal departmental email noted the company had said the $1.5m figure would make the trial “economically unviable”. A figure of $599,306 was then agreed upon.

- There was a need for greater oversight of compliance to environmental authority conditions; Mr Clarke expressed concern about the appropriateness of “reactive monitoring” by the department of novel or emerging technologies that involve high or unknown risks, ie waiting for something to go wrong, and relying on self-reporting of breaches of conditions.

- There were no formal standards in place for the design and construction of UCG wells despite the fact that UCG production bores were subject to high temperature and pressures; Mr Clarke was not convinced it was reasonable for tenures for UCG projects to continue to be granted without any obligations being imposed in relation to well standards.

- There was confusion and conflicting advice between DEEDI and DERM, and then later DNRM and DEHP, whether or not Cougar Energy required a Petroleum Facilities Licence for its Coolabunia plant.

Related articles:

|