May 3, 2016

Queensland’s “protected zone” status for Bovine Johne’s Disease (BJD) looks to have been abandoned, creating a buyer beware environment for cattle producers.

Animal Health Australia (AHA) released a statement on Tuesday saying it was now working with State Governments to implement its BJD “framework” document released in March.

This document shifts responsibility for BJD management away from regulated control to what the AHA describes as a “broader on‐farm risk‐based approach to biosecurity”.

It would now be the responsibility of producers to deal with BJD as they see fit.

This means that in Queensland, properties where BJD is detected would no longer be quarantined or subject to cattle movement restrictions.

BJD is a wasting disease which can cause chronic diarrhoea in cattle, emaciation and eventually death.

The bacteria lives and replicates in the intestines of animals and is excreted in faeces. It can survive in the soil for many months. It usually infects calves but the disease doesn’t become apparent for several years.

There is no effective treatment.

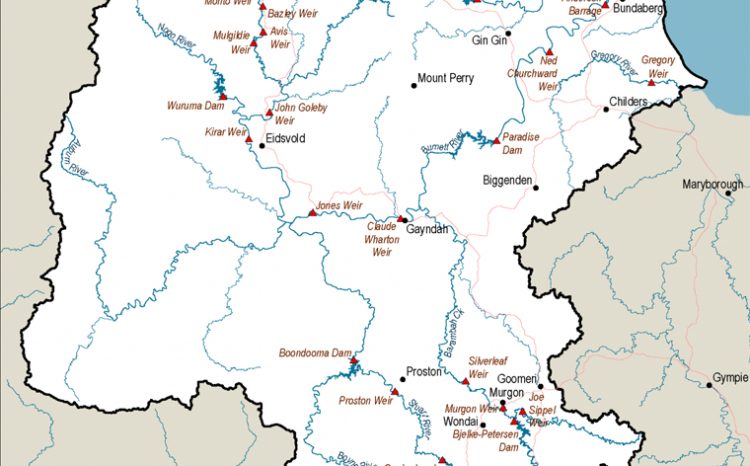

BJD is endemic in southern Australia however Queensland had enjoyed “protected zone” status under the current National BJD Scheme.

After an outbreak of BJD in the Rockhampton area in 2012, the then-LNP State Government provided $5 million in assistance to support affected producers, who restricted cattle movements.

The AHA says its “fresh approach” to the management of BJD would now “prioritise on‐farm biosecurity risk management”.

In March, Shadow Agriculture Minister Deb Frecklington expressed concerns about the new approach.

“There are real risks to Queensland from any wholesale wind-back of either government regulation and government support for producers and assistance with dealing with outbreaks – because that is what’s being proposed with individual herd/property risk-based management,” she said.

“This may suit southern States and seedstock producers and their representatives, but the wider Queensland industry would appear to be most at risk, along with Western Australia, from any major change to current protocols.”

Mrs Frecklington said she was concerned the broader Queensland breeding industry had not been engaged in the debate, and thought it needed to be before any major decisions are taken.

“Many Queensland cattle producers have been flat out dealing with drought, no cash-flow, and proposals to change the tick-line. Now they’ve got a new plan from Animal Health in Canberra to dump our stance on BJD,” she said.

The Queensland Dairyfarmers Organisation also expressed alarm.

“From an ethical and natural justice point of view, the just released Animal Health Australia document on removing regulations around BJD is probably one of the most unjust and one-sided documents I have seen in years,” QDO president Brian Tessmann said.

“Put simply, the report transfers all responsibility for managing the risk of BJD from government agencies to individual producers,” he said.

“The report goes on to say clearly that AHA’s intention is to treat BJD as an endemic disease (but) in another section of the same report acknowledges that BJD is in fact not endemic in a number of Australian regions.

“These regions obviously include Queensland, the Northern Territory and Western Australia in which the past and current regulations have served well.”

However, AHA Executive Manager of Biosecurity Services Duncan Rowland said on Tuesday the new approach had been “agreed upon”.

“It’s time to shift the thinking of industry away from regulated control of an individual disease to the broader on-farm risk-based approach to biosecurity,” Mr Rowland said.

“The State Governments are currently reviewing how they are going to address the Framework recommendations, and are working with their industries to finalise their respective implementation plans.

“Although implementation timeframes will vary from State to State, there is certainly an understanding for the need to embark upon the new approach as soon as possible.”

Mr Rowland said a communications plan would support State‐based implementation “by building awareness of the new approach and highlighting the need for strong biosecurity planning on‐farm”.

The plan would also emphasise how producers “supported by minimal regulation where required” were able to manage their own biosecurity risk status.

“This is a significant step forward for the industry with Australian livestock producers now able to take control of their own productivity and profitability,” Mr Rowland said.

He said the next steps in the implementation process would include:

- The deregulation and removal of zoning, which would occur as State Governments implemented the new Framework

- The development of tools and resources (such as biosecurity checklists, a risk profiling tool and co-operative biosecurity guidelines) to assist producers reduce the prevalence of production diseases and improve the management of these diseases

- The “enhancement” of the existing National Cattle Health Statement

- The hosting of two public forums, to meet with producers and address any questions they may have

- An evaluation of the CattleMAP and its relevance to the new Framework.

Related articles:

- MP Warns Against ‘Southern Push’ On BJD

- QDO Alarmed By BJD Proposals

- Input Sought On BJD Framework

- May Deadline For BJD Comment

- New BJD Property Identified

- $3m More In BJD Aid

- Beef Forum Backs BJD Campaign

- BJD Support Available For Graziers

- Feedback Sought On Cattle Levy

- Rally Behind Graziers: MP

- Sixty Properties Still Face BJD Bans

- Good And Bad News On BJD

- BJD Meeting In Gympie

- Agforce Welcomes New Biosecurity Fund

- BJD Band-Aid No Solution: Katter

- Voluntary Cattle Levy To Support New Industry Fund

- Two More Animals With BJD

- Ex-Chief Vet In BJD Role

- ‘Protected’ Status Key For BJD

- 150 Properties On BJD Watch List

- BJD Updates Available Online

- BJD Scare Locks Down Cattle

- MP Urges Graziers To Watch For BJD